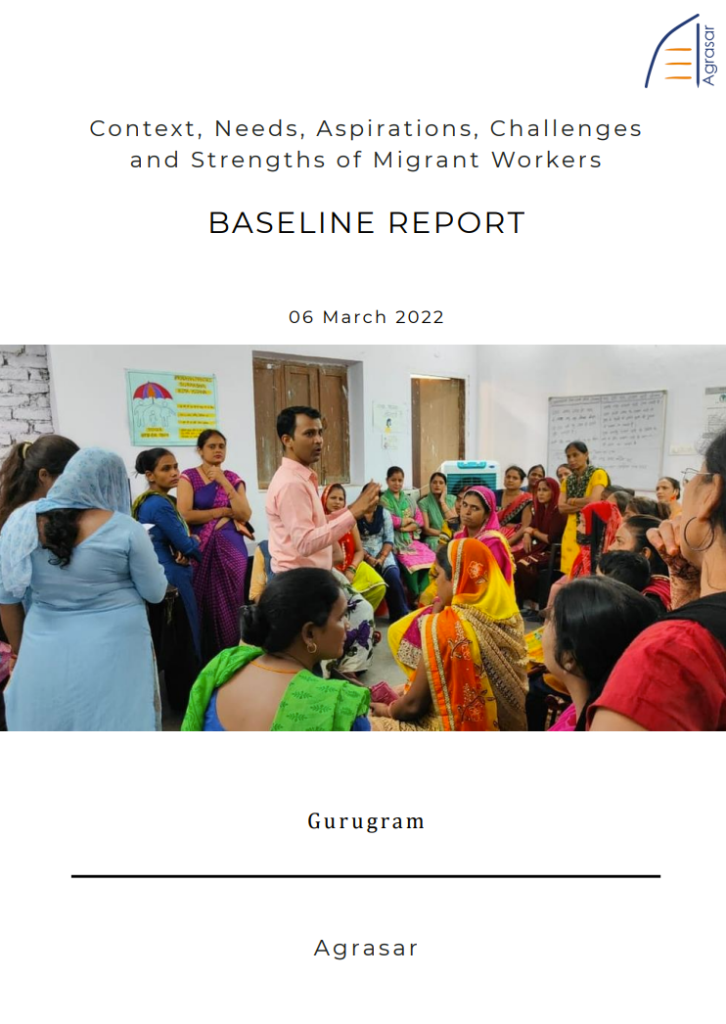

Through this research, we found that the workers and their families have nearly zero awareness, let alone connection with any Government Scheme. 94% of interstate migrant workers are found to be not linked to any government scheme. (Correct)Identity Documents themselves are unavailable; about 30% are found to be not correct, updated or linked to their mobile numbers and only 35% have a Family Id or Parivaar Pehchaan Patra without which it is becoming increasingly difficult for residents of Haryana to avail any state government schemes, get their children admitted to schools or complete the paperwork necessary to start a new job.

On the other hand, interviews with 40 companies lead to an understanding that the companies are highly resistant to register under ESI and PF. They find bypassing the compliances more viable than the compliances themselves. Besides, the collective bargaining of migrant workers is zero and their connect with the city even after years of residing is weak and that has significant consequences on this front. Aspirations are there but hopelessness is overwhelming. However, possibility of building on strengths needs more investigation and consistent & long-term attempts.

This research report attempts to understand the living and working conditions of home-based workers (a person who produces goods and services for an employer in his/her home or any place other than the employer’s workplace). While working with the community women at our Gandhinagar centre in Gurgaon, we observed that most of them are home-based workers and many of them have been facing the same problems. We made a decision to form a collective of home-based workers to bring them together, understand their situation better and enhance their connectivity. This report is to better our understanding of the worker and to strengthen our collective through knowledge.

This paper is divided into four parts. In the first part, to understand the in-depth situation of the home-based workers, we look at the root cause of the problem from the society’s perspective. The second part shows how the legal system is failing to provide protection and fundamental rights to the workers, and we see the consequences of both the societal and legal issues in the third part. Finally in the fourth part we look at the possible solutions for moving forward and the limitations of the study which should be worked upon further.

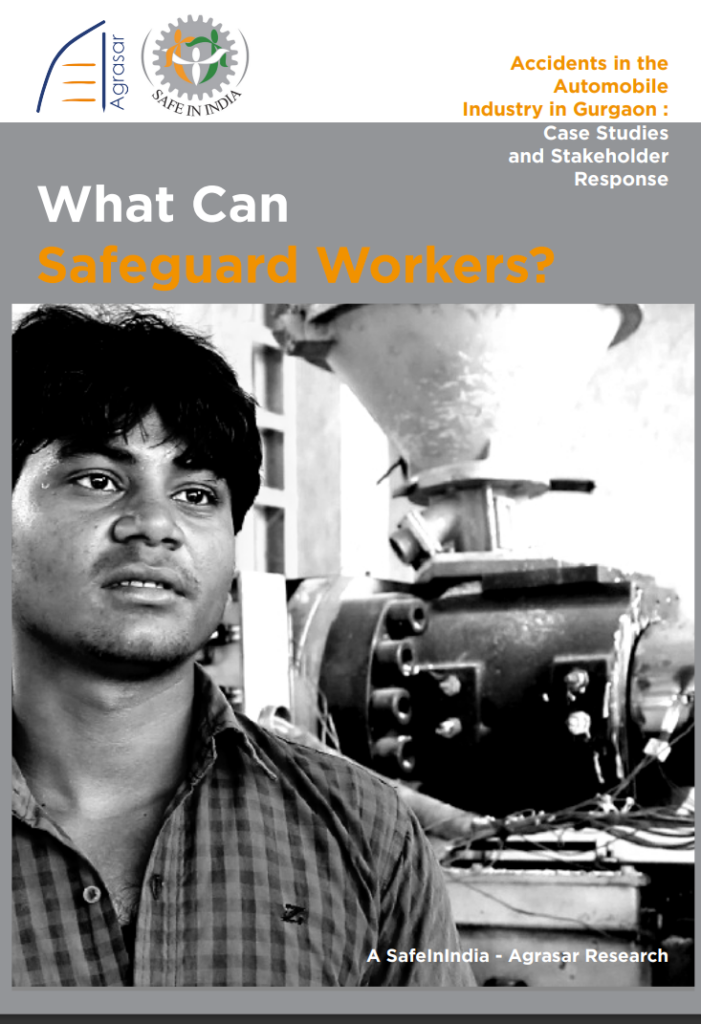

India’s auto industry is one of the largest in the world and growing fast. Despite, and to some extent due to, its growth and success, more than a thousand workers meet with serious accidents just in the Gurgaon–Manesar belt every year. While laws regarding workplace safety, post-accident care and compensation do exist, there is an absence of effective institutional mechanisms to support their implementation. This had led to hazardous working conditions, a low level of safety consciousness and training and inadequate post-accident treatment, compensation and rehabilitation.

While important literature is available on the Indian regulatory environment, relatively little analysis using ethnographic tools to capture the experiences on injured exists. Therefore, as a first step, Agrasar and Safe in India conducted this research in 2015 to understand the causes and effects of (mainly) crush injuries suffered by workers in the automobile manufacturing sector in Gurgaon-Manesar belt.

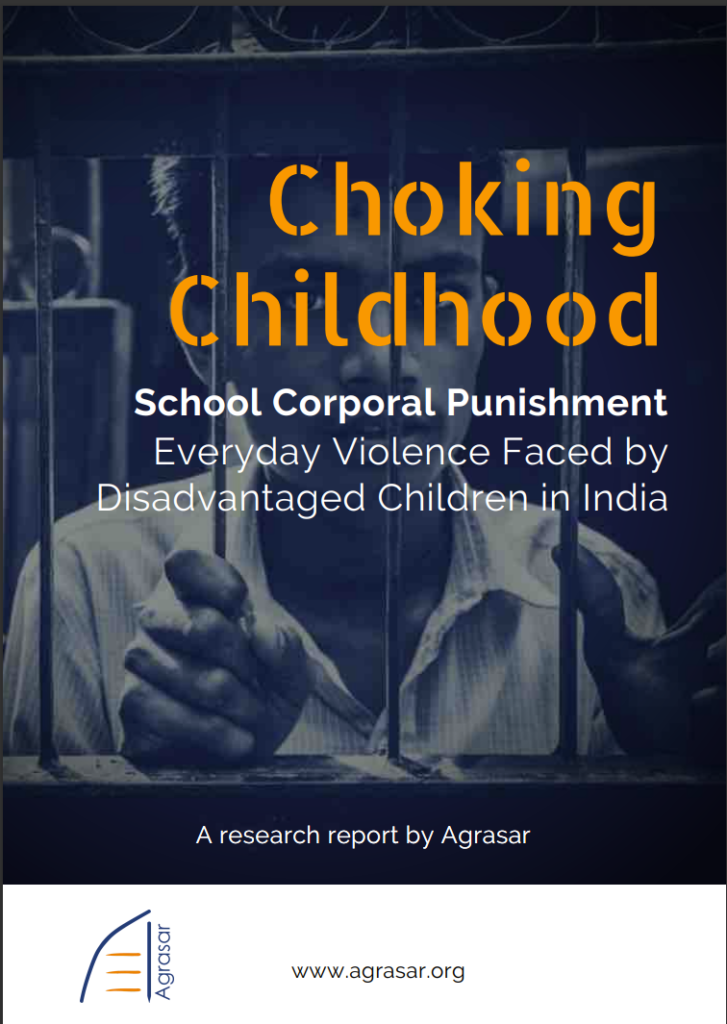

Corporal Punishment: Everyday Violence Faced by Disadvantaged Children in India. During 2017 and 2018, Agrasar has done comprehensive research to understand the magnitude, frequency, forms, and risk factors driving the practice of corporal punishment in government schools in Gurugram. Our research report “Choking Childhood” presents a grim picture: Almost all disadvantaged children experience physical and verbal abuse by teachers, around half of them on a daily basis. In some schools, 88% of students are beaten regularly. 70% of parents punish their children when they find out, as a result of which children no longer share school-related experiences at home.

The risk factors that put marginalized students at risk include low-income and “migrant” backgrounds, government schools that are often characterized by an environment that fosters violence against children, and our social norms that justify physical and mental abuse of children in the name of discipline.

This Manual is a compiled and abridged version of the major 14 labour laws that exist in the country along with the recent amendments as of July 2020. Each law is preceded by a scenario which will allow the reader to connect further with the everyday issues faced by workers.

For better understanding, readers should try to apply the major sections of the law to the scenario and develop their own understanding. The document is designed for perusal of development practitioners for whom understanding needs to be in a practical manner to be further disseminated through the community.

In May 2020, Agrasar, in partnership with Safe in India, conducted a rapid survey of 100 migrant workers for their April 2020 wages and found that despite the government announcement regarding employers paying their employees in full for the months of March and April, 75% of the migrant workers were yet to receive their salary.

77% these workers remained in their pre Covid-19 place of residence hoping to get a call soon but only half of them received a call from their previous employer. In May 2020, the government withdrew this mandate leaving the migrant workers to fend for themselves.

This report brings in insights from a rapid survey of 108 migrant workers to understand their employment status as at mid-Jun20. This survey shows that almost half of these workers are unemployed, despite the majority of this sample being skilled workers. Even those who have found employment have a large proportion whose incomes are much lower than their already meagre pre-COVID19 salaries. Many of them do not want to continue in the same jobs. Of the unemployed in Gurugram, majority are ready to do a lesser paying/lower skilled job but are uncertain of job prospects and most have borrowed money from landlords and friends/family to survive. Those who have gone back to villages are still mostly unemployed. In fact, money, not Corona virus, is the main concern for both the employed and the unemployed. If this is the state of this largely skilled sample of workers, one can only imagine the even worse status of the less skilled workers/daily wagers. There is a need for a more co-ordinated employment approach by the government and industry to improve this situation and a desperate need for cash-transfers to the unemployed until they are back in gainful employment. Employers also need to do better to retain their workers and for better productivity.